On 15th June 2015 Tom addressed a workshop at the NCVO Evolve conference on ‘Choosing a Corporate Partner’. Sharing a platform with the pioneer of responsible business, former BITC head Dame Julia Cleverdon, he used the opportunity to launch his report ‘The Company Citizen‘. Here is Tom’s speech…

You don’t need me to tell you what charities want from partnerships with business:

- Capacity to deliver a service better.

- Social capital: the time and skills of volunteers.

- And access to resources you can’t afford yourself.

Alternatively, that proxy for everything: Money.

So let me start with three statements of the bleedin’ obvious:

- Many big corporates know what they want from charity partnerships: at the very least, it’s a good name and a salved conscience; at best they seek employee engagement, skills development and access to innovative ideas and practices. Sometimes, they even want to help relieve suffering and indignity and support social change.

- Big corporates tend to go for big partners. It’s easier that way.

- Not all corporates get it right; some partnerships are superficial, created to tick CSR boxes, whilst others are well meaning but misguided – such as where the company need for team building outweighs the opportunity to create positive socially valuable outcomes.

I don’t like ‘Charity of the Year’ arrangements, especially where big corporates (and potentially the biggest short term gains to the charity) are involved. Why not?

Because the bidding process can be competitive and potentially costly to charities whilst not necessarily producing rational partnerships – popular causes tend to win employee votes at the expense of the matching of missions.

The converse is also true: that charities supporting unpopular causes, like homeless people, asylum seekers and AIDS sufferers, tend to miss out.

When you’re a Charity of the Year, who are your fundraisers talking to? Who are the top CSR executives in the company talking to?

They’re talking to next year’s potential partners, not making the most of this year’s.

A great example of mission matching is the partnership between Boots and Macmillan Cancer Care – and matching is at the heart of a sustainable relationship. A Charity of the Year is, by definition, the antithesis of stability.

Companies, by and large, are not seeking to be altruistic or philanthropic. I don’t like the phrase ‘giving something back’, either, as it’s a tacit admission that something was taken in the first place, possibly illegitimately.

So… companies can be a force for good. But… there must be something in it for them. A business case.

A business case is not just about the ‘bottom line’, although marketing opportunities, reputation and even innovation can all be legitimately linked to charitable or community activity.

A good company is a good neighbour – but also a good employer.

A good employer cares about employees and wants to see them do well. Be happier at work. Be more creative. Take less time off through sickness. Act as ambassadors for their company.

And to be more productive.

And there’s a lot of evidence that all of these qualities can be boosted when an employer encourages employees to be more engaged in the communities around them.

Slide 2 – Engagement data

Employees’ View / I would speak highly I would be critical

Status of my employer of my employer

Not aware of

Community 50% 23%

Engagement

Programmes

Aware of them 65% 19%

but not involved

Both aware and 82% 13%

involved

These figures [from Canadian research in the 1990s] speak for themselves.

Where a community engagement programme exists, employee morale (and productivity) is boosted – whether that employee is actively taking part in it or not!

A community engagement programme should not just paint walls or tidy old folks’ gardens.

Because there’s something else that good employers are increasingly looking for: for employees to enhance their skills through community engagement; both hard (work-related) skills and softer, personal, ones.

And employees themselves, especially the so-called millennials, are not only seeking a greater purpose to their work – making money or widgets is no longer enough – but they’re more likely to buy ethically sourced products than they used to be, too.

Everything I’ve said applies to corporates. Indeed, there’s a phrase for it: ‘corporate social responsibility’. A phrase I don’t use much because, again(!), I don’t like it.

CSR means all things to all people, from the most flimsy and passing acquaintance with communities to the most profound long term and meaningful relationship.

The phrase has become almost meaningless.

I know a Chief Executive of a big, people-centred charity who’s often wooed by potential corporate partners; if the representative comes from CSR or PR departments, he won’t talk to them.

If they’re from HR or procurement, core business functions, he will.

There’s a growing belief within business that community engagement, CSR if you must, ‘company citizenship’ as I call it, should be a mainstream purpose of business and not a peripheral.

You only have to look at Unilever and the leadership of Paul Polman there, or Mike Rake at BT, or Ian Cheshire, formerly of Kingfisher, and yes, even Richard Branson, to see that there’s an appetite for this. Add to them Wates the builders, Interserve, Timpsons, Gregg’s and Andrews the estate agents: ‘company citizens’ all.

However, the UN Global Compact reports that whilst business leaders generally are increasingly talking the talk, too few are yet walking the walk.

And they must: for, as Al Gore warns us in his book, ‘The Future’, if business doesn’t take play its part on tackling climate change and on rebalancing the global economy to defeat hunger and poverty within the next five years, the consequences will be disastrous.

But here’s another reason why ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ isn’t the way forward: the clue’s in the name.

Slide 3 – SMEs

99 of every hundred businesses in this country are not corporates.

99 of every hundred businesses in this country are not corporates.

Together, almost five million SMEs employ half of the private sector workforce and produce 60 per cent of its wealth. Even if you exclude businesses which are simply self employed individuals, or companies with no employees, then there are two million employers in UK – or about 3,000 in each Parliamentary constituency.

Ten years ago BITC found that SMEs viewed the word ‘corporate’ in the phrase ‘CSR’ as meaning ‘Not for me’.

Two years ago in a survey of small businesses in Yorkshire I found exactly the same.

But when I asked about ‘community engagement’ I got a different answer: most SMEs thought it was right for businesses to get involved in communities and only a fifth said it was ‘nothing to do with us’.

And more than half of those who agreed thought that they could, and should, be doing more than they currently do.

So, why don’t they?

The usual arguments are shortage of time and money.

‘Time’ is no excuse – it’s how you think about these things that matters, not how long; and ‘money’ ignores the possibility of justifying activity with a business case, as I’ve described.

The most popular form of community engagement was the giving of raffle prizes and small cash donations – and these were usually reactive, responding to requests from charities, not proactive.

That’s not to say that employee volunteering doesn’t happen – it does, but it again reflects SMEs’ ‘shortage of time’ compared to corporates, who benefit from economies of scale.

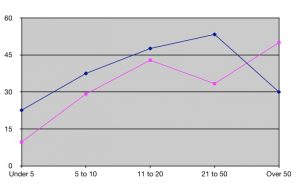

Slide 4 – VOLUNTEERING GRAPH

Let’s distinguish between ‘time volunteering’ – essentially low-skill or mundane tasks – and ‘skilled volunteering’ in which an employee uses or develops their workplace skills in a good cause.

Let’s distinguish between ‘time volunteering’ – essentially low-skill or mundane tasks – and ‘skilled volunteering’ in which an employee uses or develops their workplace skills in a good cause.

Here we can see that skilled volunteering (top line) happens even in some of the very smallest businesses (x axis = number of employees), where time volunteering hardly does at all.

As companies grow in size, the incidence of both rises; but above 20 employees, time volunteering continues to grow but skilled volunteering falls off. (Source: The Social SME, Levitt, 2012)

Why?

Because these companies regard the team building aspect of garden clearing or wall painting as more important than any social contribution it may make.

Some charities actually reserve walls to be painted by corporate volunteers… just to find them something to do.

In Australia, a major bank has banned team volunteering – because whatever social value morning sessions produced, the afternoon sessions – no doubt after a few tubes of amber nectar – produced mass absenteeism and lower standards of conduct, causing damage to the bank’s reputation.

So, a good corporate citizen provides a variety of opportunities for their employees to choose to engage, utilising different skills and temperaments, different degrees of commitment, at different times – from listening to school children read to growing a small charity by helping create a business plan.

This is how best to help –

Slide 5 – WALL CARTOON

So… any corporate creating a pool of engagement activity, involving cash and kind, time and talent, head and heart, will probably need more than one charity partner.

It will need a network of partners within the community it shares with them.

And if that network can be created for one corporate within a community it can be shared with others.

And if it can be shared with other corporates then it can be shared with SMEs, who have more employees in most communities than the corporates do, but for whom the creation of their own volunteering pool is, frankly, too difficult and not yet a priority for them.

But in some parts of the country it is happening: in Tameside, Swindon, Merton and the City of London to name but four. My latest report is called ‘The Company Citizen’ –

Slide 6 – COMPANY CITIZEN

– it looks at how 14 of these networks have started, how they’ve developed their offers and the challenges they face (I’m pleased to see Alison from Stoke on Trent and Helen from Oxfordshire here in the audience).

And it’s launched on the web today!

Charities cannot simply approach businesses with begging bowl in hand any more.

You have to offer them a deal, a partnership, however transient; make it clear that it’s in the interests of business, large and small, to better engage with communities – and that charities and voluntary organisations are the means through which this is possible.

Because promoting partnerships through company citizenship is in the best interests of sustainable and responsible business.

In an era of austerity and public spending uncertainty it’s in the best interests of charities.

And, ultimately, growing the capacity and skills of the voluntary sector in this way is in the best interests of the people who matter most, our beneficiaries.

END