On 6 September 2015 Tom Levitt addressed the ISIRC [International Social Innovation and Research Conference] conference in York on the relationship between personal debt, wellbeing and social progress. In particular he sought to explain the purpose of the new charity of which he is chair of trustees, Fair For You, which will provide low cost ethical loans to purchase household necessities for low income families. The conference brought together 140 academics (mostly) and practitioners for three days.

Here’s the paper… 150906 FFY wellbeing TL – and here’s the speech which accompanied it:

I don’t need to tell this audience about the scourge of poverty, growing inequality, the poverty premium and their negative impact on the wellbeing of individuals and communities.

I do want to tell you just one way in which these issues are being tackled: through a low cost, nationwide, ethical lending institution.

Fair For You is a Community Interest Company, wholly owned by a charity, with a lending licence.

It will be launched in early 2016 with pilots starting in just a few weeks time.

I’m the Chair of Trustees of the charity and a non-executive director of the CIC.

Let me illustrate the problem that we are trying to resolve.

Imagine… you’re a single mother in her thirties with three children under ten.

You’ve got a part time job that fits with your children’s schooling and child care.

You’ve a mobile phone but no credit card, a basic bank account but you can’t have an overdraft.

You can have direct debits on your account but if they fail they’re expensive: paying for electricity on a pre-payment meter – conventionally regarded as the costliest way to buy energy – might be better for you than having just one direct debit fail each month.

There’ve been times when your children have had just toast for their evening meal because you’ve rent to pay the next day so you couldn’t afford anything else.

You’ve never been in arrears and you believe that commitments are commitments, you’d never take on a debt you didn’t intend to repay.

You find this situation… heart-breaking.

Then, one day, your old washing machine dies a noisy and juddering death.

Those three kids are hard work! Even if there was a launderette in your neighbourhood – there isn’t – it would cost you more than £10 per week (not to mention the inconvenience) to keep up with the stream of dirty clothes they get through.

You’re going to have to buy a washing machine; you don’t want a second hand or a refurbished one – who knows how long it would last? And you don’t know what’s been in it… besides, you don’t want other people’s ‘charity’, that’s undignified.

You’ve heard that although the Council used to give people like you grants to help buy a washing machine that’s all stopped now. It’s the cuts, you know.

Whatever else you lose, being on a low income, you want to preserve your dignity.

You notice that Curry’s have a range of washing machines for under £250 and they’ve got credit plans… you don’t really understand this ‘APR’ business but your neighbour says she does and that 20 or 25 per cent interest is cheap… but it sounds a lot.

Then you find that Curry’s want a 10 per cent deposit which must be paid by credit card (which you haven’t got) – but they’d regard you as an unacceptable risk and wouldn’t lend to you anyway…

Then a brochure comes through your door…

It’s glossy, attractive and seems to have some good offers on the cover. It’s from a new shop, just opened in your area. Worth a try?

You take the children to the store after school one day; there’s a range of washers for ten pounds a week or less – cheaper than the launderette – with no deposit needed.

You can afford ten pounds a week – at a push – and although you don’t want to buy from the bottom of the range you certainly don’t want the all singing, all dancing kind either. But you do want the reassurance of a recognised brand.

You find the model for you – it’s white, most of them are, and only £8 per week, but your 8-year old daughter by now has her heart set on the red one (which is £2 a week dearer) and the salesman suggests that you may need a bigger capacity machine, what with the three children, and a faster spin speed, to save time… how to make the choice?

You eventually decide on a £10 per week one (but it’s not red, to your daughter’s chagrin) and the salesman offers you their support package too – well, he doesn’t actually offer, he insists. The package is the only one available; it includes a three year warranty, insurance, delivery… everything you need, in short, to put your mind at rest.

There’s a very basic credit check (‘We can’t provide this service to everyone!’) but you’re approved and given the standard warnings: ‘failure to meet regular payments…’ you know the drill.

The machine gets delivered and installed and you’re happy… reassured, relaxed, you’ve covered all your bases.

Until someone points out that you in signing up to £10 per week for three years you’re paying roughly £1,500 for a machine that Curry’s is selling for £250. At 65% APR – whatever that means – but wasn’t Curry’s 20 per cent? There’s a big difference, but it’s academic as you wouldn’t have got a loan from Curry’s in the first place.

|

Typical cost |

Cost to low income family |

Reason for higher cost |

Difference |

|

| Basic cooker |

£239 |

£669 |

High interest loan |

£430 |

| £500 loan (paid off on time) |

£500 |

£750 |

Doorstep lender |

£250 |

| Cash: 3 x £200 cheques |

£0 |

£36 |

No bank account |

£36 |

| Annual energy bill |

£881 |

£1,134 |

Poor value tariff (e.g. prepayment) |

£253 |

| Home contents insurance |

£67 |

£99 |

More expensive insurance area |

£32 |

| Car insurance |

£310 |

£598 |

Ditto |

£288 |

| Figure 1: The Poverty Premium (After Save the Children, 2011, quoted in Hirsch, 2013) | ||||

I don’t think there’s a starker example of the poverty premium – and this illustration from Save the Children shows it clearly.

All aspects of this story are borne out by research carried out for Fair For You in Birmingham using focus groups of women with experience of having – and also of being refused – high cost loans of this nature. In describing high cost lenders they used words like ‘extortionate’, ‘vultures’ and ‘take advantage of you’.

They particularly resented Brighthouse’s policy of adding a £5.50 charge per item every time a payment was even a day late; if that’s not a poverty premium, I don’t know what is!

There are possibly 5 million households in Britain in this dilemma, this logical trap: they can’t afford to buy the cheapest option and are forced to pay premium prices. The poverty premium adds ten per cent to the cost of daily living in a poorer family, compared to a richer one which can afford to buy cheaper.

It’s really no surprise that poverty is associated with depression, suicide, poor general health, lower life expectancy and abusive and self-abusive behaviours. And, of course, with debt.

Last year the Government responded to concerns by MP Stella Creasey and others by regulating the pay day loan market, those high cost personal loans epitomised by Wonga, to the extent that Wonga was obliged to write off some £30 million in loans where the conditions were no longer regarded as reasonable.

Pay day loans are cash loans made to an individual: what I’m talking about are ‘rent to own’ loans where no cash changes hands and the provider of the goods – in our example the washing machine, though it could have been a fridge, television, cooker or games console – retains legal ownership of the product until payments are complete.

This makes repossession easy, should the customer default on their payments as up to a fifth of such customers do, ending up with neither their money nor a washing machine.

Back last autumn the Chancellor said he would review the regulation of the rent to own market but in a less trumpeted announcement earlier this year he confirmed that no changes are being proposed. It’s apparently acceptable to charge a poorer family £1,000 more to buy a £250 washing machine than a cash or credit card customer would have to pay.

Yet, in a sense, I think he’s right because regulation – or at least, regulation alone – is not the answer.

What happened in the pay day loan world was that the market adjusted to the new regulations: companies saw them as a challenge, a sort of reality TV game; in order to stay in the market they had to adapt, get round the new regulations rather than enter into the spirit of them.

Some may have gone to the wall and some customers may have transferred their allegiance away from the Wongas of this world to the ‘baseball bat bullies’ of the informal loan market. We just don’t know, partly because it’s too early to say and partly because it’s terribly difficult to know what’s happening in the darker corners of the ‘grey economy’.

Hang on a minute, you might say – there is competition in the personal loan market – both from the credit union movement and from the newly established Community Development Finance Institutions, the CDFIs. Credit Unions in particular are established providers of small, low cost personal loans to poorer areas…

Yes, they are, and would that the credit union movement was as well established here as it is in Ireland or America. But neither they nor CDFIs are equipped to manage rent to own loans or to do so at scale or, indeed, to establish themselves within that part of the economy where the need for the service is greatest. In fact, credit unions have a fairly conservative lending policy; and you must be a saver before you can borrow.

As poverty has got worse – in-work poverty in particular – the lending ratio of credit unions has plummeted: per £100 of assets they were lending £80 ten years ago but only £60 now.

If you then add to that the fact that whilst credit unions are restricted to a maximum APR of 42 per cent some CDFIs have an APR of over 100 per cent, almost double that of the rent to own providers, a figure that can only be sustained for very short term loans which are not appropriate for major household purchases like fridges or washing machines for low income families.

If credit unions and CDFIs were the answer they would have stepped up to the mark by now…

In short, regulation without effective competition will not achieve the desired effect.

This is where Fair For You comes in.

Fair For You will be a national, on-line, low cost ethical lender targeted at those just below the conventional banking and credit threshold.

However, it will not be a panacea; many who cannot get loans from existing institutions will not be able to get credit from Fair For You, either. But there will be those to whom we will lend – using a propensity to repay calculation rather than a standard creditworthiness one – to whom banks and credit unions might not. And that’s a growing – and desperate – market.

Fair For You will supply a range of essential household goods through one or more major electrical online retailers with an eye for ethical business – and our customers will get the same high levels of customer service as theirs do.

The goods we sell will be utilitarian rather than luxury items – but they will be recognised brands, energy efficient and with the maximum manufacturers’ warranty, so making it unnecessary to sell additional warranties at the point of sale.

People who we turn down for credit will be referred to a partner charity for a benefits check and advice on managing their finances; similarly for people who default, for whom with us there will be no automatic penalty. We will do almost anything to extend, reschedule or even briefly suspend a loan to bring payments back on track; repossession to us is an indication not of our customer’s failure but of our own.

We will have no high pressure sales people, we won’t telephone your neighbours to chide you to pay when you’re in arrears – oh yes, it happens – and our interest rates of 3 per cent per month, 42 per cent APR, will match the maximum allowed to credit unions, thereby sending them a message which says ‘we are not in competition with you’.

This way, that same washing machine that was £250 on the High Street, £1,500 (that’s £10 per week for three years) with Brighthouse will be £7 per week for one year – that’s £350 – with Fair For You.

That saves the family £1,000 over three years… bringing down the cost of poverty.

In addition, we’ll invite our customers to pay a little more which will go into a credit union savings account in their name, so helping them to become more creditworthy in the long run.

My profession is consultant to companies, charities and government on ‘using the tools of business to create public good’. In my role as chair of trustees of the Fair For You charity, which owns the lending business of the same name, I believe I am putting those values into practice.

I want to say a little about why this matters and how it fits into the global scheme of things.

I want to pay tribute to some excellent work by Professor Michael Porter of Harvard and my old friend Michael Green of London for work they call the Social Progress Index, launched a couple of years ago.

The ‘health of a nation’ is often measured by Gross Domestic Product, introduced in the 1930s, recognised internationally in the Bretton Woods agreements of the 1950s and criticised as inadequate as a holistic measure of progress by its inventor, Simon Kuznets, as early as the 1960s. The Social Progress Index takes 52 internationally established measures of social (rather than economic) progress in three fields:

- Basic human needs,

- Foundations of wellbeing and

- Opportunity.

The 16 criteria earmarked ‘Foundations of wellbeing’ can be, according to Porter, classified into four categories:

- Access to basic knowledge,

- Access to information and communication,

- Health and wellness and

- Ecosystem sustainability

whilst Health and wellness is itself represented by measures of:

- Premature death from non-communicable disease,

- Life expectancy,

- Obesity,

- Deaths attributable to outdoor pollution and

- Suicide.

The most successful country in the world by each measure is given a score of 100 and the least successful zero, with others ranked according to their progress relative to these two markers.

Intuitively we’re not surprised that northern Europe, North America and Australasia come towards the top of the ranking and sub-Saharan Africa dominates the lower end; but there are significant differences from the GDP rankings. The top ten includes five Scandinavian countries but not UK (11th), Germany (14th) or USA (16th).

Another surprise is that the very poor but socially progressive Costa Rica is 28th out of the 133 for which full data was available, ranked far higher than its economic performance would suggest.

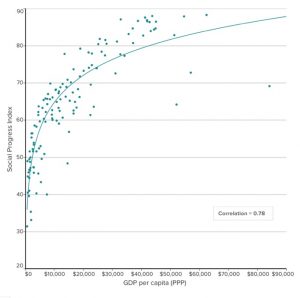

What is particularly interesting about the Social Progress Index is its correlation with GDP. As this figure shows, in poorer countries there is a strong correlation between increased levels of GDP and increased levels of social progress but this is not as marked in better-off countries, where even the addition of significant GDP through economic ‘success’ creates little discernible advancement in social progress. Even when the three strands are disaggregated the same phenomenon is shown in each field; we can conclude that Wellbeing is linked to economic success in poorer countries but less so in richer ones.

But it gets better. Since the Social Progress Index was launched it has been formally adopted, alongside GDP, as a measure of national progress by a number of countries, starting with Paraguay and now including Brazil, where they have discovered that when Social Progress is measured on a sub-national level the same patterns can be seen and same conclusions drawn; so in USA it’s to be used at state level in Michigan, in Colombia for measuring progress on a city by city basis and across the regions of the European Union similarly.

If this correlation is evident at country, regional and city levels then perhaps it works at a community level too: increasing economic activity, relative wealth and money flow will have a bigger impact on a poor community than on a more affluent one. In which case, retaining money within a deprived community and allowing it to circulate, as Fair For You allows, could have a very significant positive impact on the wellbeing of individuals within that community.

The phrase ‘living in poverty’ is generally accepted to mean those with a household income of less than 60% of national median income.

By whatever measure we use, not only is this number growing in Britain but there has been a frightening rise in the number of people living in in-work poverty – over half of those living in poverty (and perhaps two thirds of children living in poorer families) live in households where at least one adult is employed.

The alleviation of poverty must be a prime goal of any civilised society.

The exploitation of poverty must, equally, be frowned upon and guarded against within that society.

But it’s not.

We’ve seen how the poverty premium can be reduced by practices like those of Fair For You within a poorer community and we have seen that social progress is linked to economic progress in poorer communities (though much less so within affluent ones).

We have seen that in buying one essential washing machine Fair For You can save a typical family in poverty £1,000 over three years.

But such families tend not to buy one item at a time.

And within a given community there will be many families in similar need.

And there are many of those communities, containing possibly two million households in Britain, who are excluded from normal commerce and the trappings of – not affluence, but adequacy.

Let’s assume that over the next five years just half of those families buy just one item, a washing machine or a fridge, from Fair For You.

When was the last time you heard a Government minister say “We’re going to put £1 billion into the economies of our poorest communities over the next five years”?

You didn’t.

But that’s an outcome that Fair For You can help achieve, and our impact will include helping a whole stratum of society, the underprivileged, become more affluent, with raised levels of wellbeing and financial competence and living in more sustainable communities.

Because, as they say, they’re worth it.